In the News

Posted on December 14, 2022

This article was originally published by Jodi Schwan of SiouxFalls.Business.

Darin Hage knew the crisis team at Journey Group was scheduled for a drill one recent afternoon.

But the vice president of Journey Construction wasn’t thinking of it when his phone rang around 1 p.m. and he saw the caller ID: Tamara Knecht, wife of Journey CEO Randy Knecht.

“I thought, ‘Tamara Knecht? Should I take this?’ So I picked it up, and Tamara definitely played the part. My jaw dropped.”

She told Hage that her husband was on a plane to Spearfish to visit Journey’s Ainsworth-Benning operation. The plane had gone down, and his condition wasn’t known.

“It was hard to process what was happening,” Hage said. “I had just met Randy half an hour before, so I was able to realize it wasn’t real, but it took Joel to give me a hint it was a drill because Tamara didn’t.”

Joel Van Ekeren is Journey’s safety director, and every quarter he puts together a lifelike simulation drill for the team to practice responding to emergencies.

“He tries to make it as real as possible,” Hage said. “Everything is staged to be as much of a real-time situation as it can be.”

In this case, Hage recovered from his shock and began to organize a response. The company’s Boyce Training Center became central command for the leadership team, HR, marketing and communications. Some team members joined through videoconferencing – including from Ainsworth-Benning – to reflect what likely would happen in reality.

“We knew it was a drill, but it can feel very real,” Hage said. “So it was an exercise in how the team works together, communicates in a chaotic environment and keeps all the different factors we need to consider in play.”

As the exercise progressed, the team learned Knecht had not survived the crash. They had to determine how to reach multiple audiences – including a mock interview from SiouxFalls.Business – and work through HR-related challenges, from supporting employees to looking at succession.

“I think they did really well,” Van Ekeren said. “I was really proud of how Darin rose above that emotionally. I had certain things I was looking for from the team, and they checked all those boxes. They have learned as a team how to manage crisis, which is the goal. They don’t talk just to talk. They do so in a quiet way to not interrupt the thoughts of their team, and a year and a half ago, it would have been pretty chaotic. They’ve come a long way.”

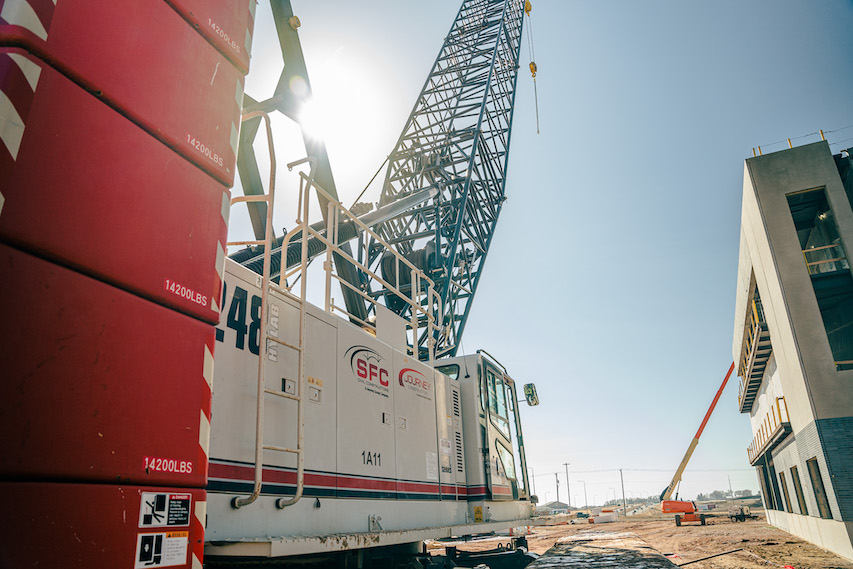

That’s thanks to a wide variety of quarterly exercises developed by Van Ekeren. While one involved responding to a cyberattack, most of them involve job site-related incidents, like one recently that used the Avera medical center under construction in east Sioux Falls.

“In that scenario, one of our steel erectors went down with a possible heart attack. We got the fire department involved in the simulation, so they were there and worked with our crane operator,” he said. “We have rescue baskets we’ve never used, so we wanted to rig up our basket and lower our guy from the roof of Avera East. Our crane operator had to communicate with hand signals and two-way radios, and they worked with rescue crews to lower him.”

But before the idea of this more intense crisis drill came to fruition, the original plan looked entirely different.

At first, the plan was that Knecht would be lowered from a building.

“I was out of town, so I was kind of disappointed,” Knecht said. “But then Joel said, ‘We’re going to do a crisis drill that involves you.’ And I said, ‘OK what is it?’ And he said, ‘You’re going to die.’”

While he laughs as he says it, Knecht said there’s significant value in practicing for such an event.

“While some people get anxious, nervous and flustered in times of crisis, Joel gets calm. That’s where he thrives. I thought the idea was great because it forced us to think through things we hadn’t talked about.”

Van Ekeren is a retired firefighter and emphasizes the importance of planning for worst-case scenarios.

“It’s very rare for a construction company to have a crisis team. But when something happens, we want to take care of the injured person, but we also want to help the team running the job site bring order to the chaos and protect each other and protect the company,” he said. “We were at a national conference with probably 250 people, and my colleague and I were the only ones who raised our hands when asked who has a crisis team and does drills. No one else is doing this. It sets us apart.”

To reinforce the message, the Journey team even has QR code stickers in hard hats and on laptops that lead team members immediately to the company’s crisis plan.

“Joel just continues to step it up in terms of the next surprise he’s going to put on us,” Hage said.

“We keep saying we’re going to create one he doesn’t know about and see how he handles it. But in all seriousness, since we started, our team has really commented on what a difference it makes when you do have situational things come up. You’ve been through mock drills, you go back to the playbook and realize you have the processes in place, and there’s a whole team of people ready to take care of whatever is needed.”

For Knecht, after watching the team role-play through his own death, he realized that although Journey has spoken about succession planning, it hadn’t yet set up a “what if” scenario that would involve his sudden passing.

“The big takeaway for me was asking myself, ‘Who is going to step in and start making decisions?’ We need to be ready. And what’s amazing is, when you practice things like this, where everyone has roles, it will go better than being unprepared.”

He also added that sitting in the room observing everyone from his wife to his colleagues made the scenario even more real, although everyone knew it was a drill.

“No one looks forward to practicing these things. It’s hard and puts everyone in an uncomfortable situation, but I’m proud of our team for handling it so well.”

To view the original article, please click here.